I'm not sure if all teachers feel this way, but when I look back at my first year of teaching, I cringe.

My first year teaching I had three preps, but four groups of students. Two groups were labeled "advanced" and two were labeled "academic." I then saw each group again for half a period for a writing lab. While I had a lot of curriculum problems that first year (which took another year or two to work out), the biggest problem was differentiation.

Here's a scary example of how I made the advanced work "harder:" The advanced students had to supply the authors of the texts we read and match the titles and plots, while the academic kids only needed to match titles and plots. Wow. Why didn't someone stop me?

Looking back now, supplying the authors and matching the titles and plots both seem meaningless, but it sure did make for a test that was easy to grade! However, the fact that I thought adding more to memorize would make a course more advanced, that appalls me now. I'm positive that everyone around me let this type of mistake slide because I was a first year teaching, which by definition means learning everything on the job.

As the years went by, I stopped having students memorize information almost entirely. I lost a lot of my fun material when I stopped giving tests and quizzes. No more fun bonus questions, review games, or prizes because we no longer had content to drill for a test. No more tests because we no longer just retold information. It was hard to let go of these fun aspects of my

teaching, but I enjoyed my new content so much more when I was no longer

rewarding the wrong type of performances. Why reward a student memorizing when he can use all the sources I've been supplying to look information up? Instead, there is no need to memorize who the author is because I'm going to let you have a copy of the text as you write me an essay showing some critical thinking on the text.

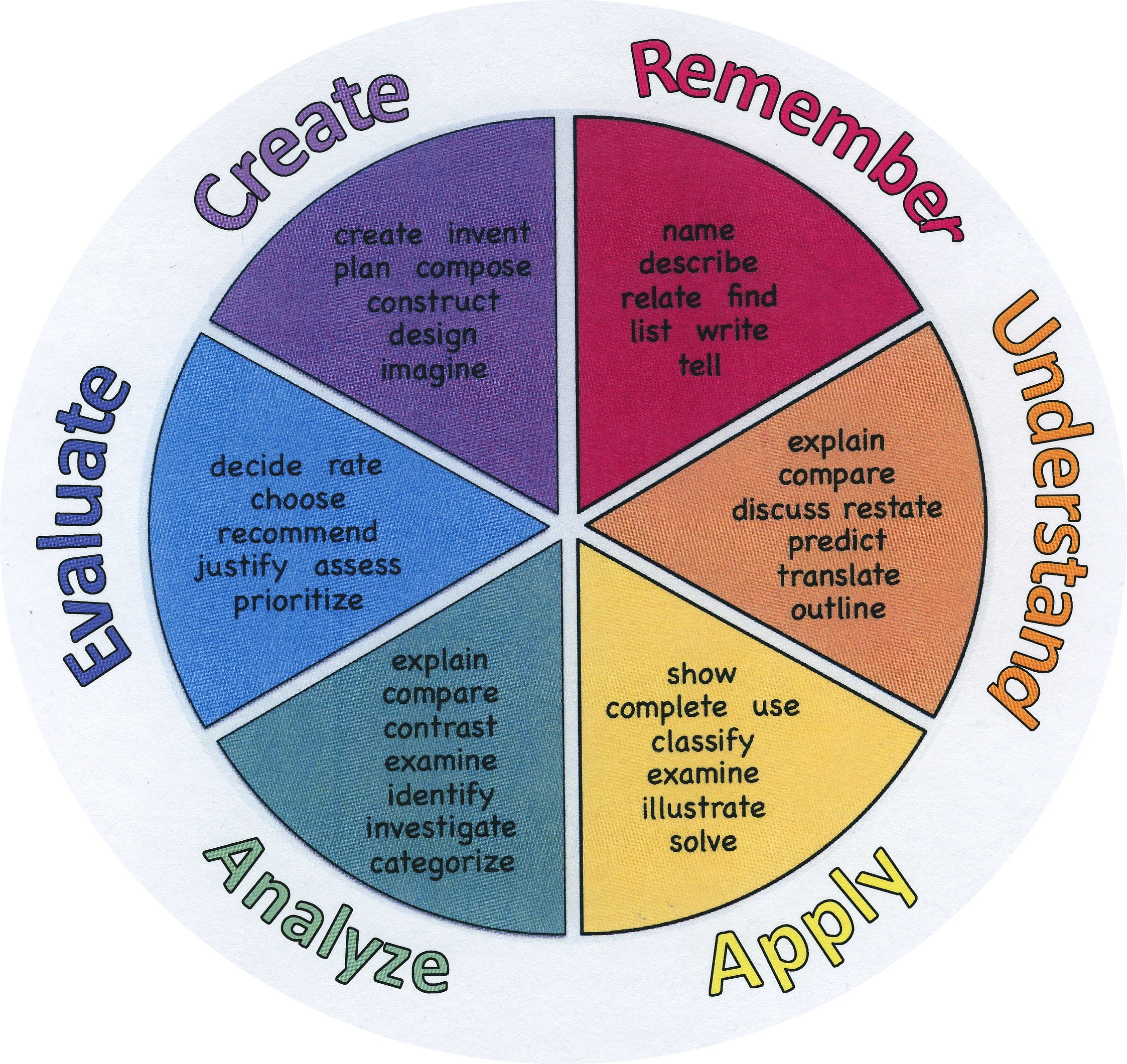

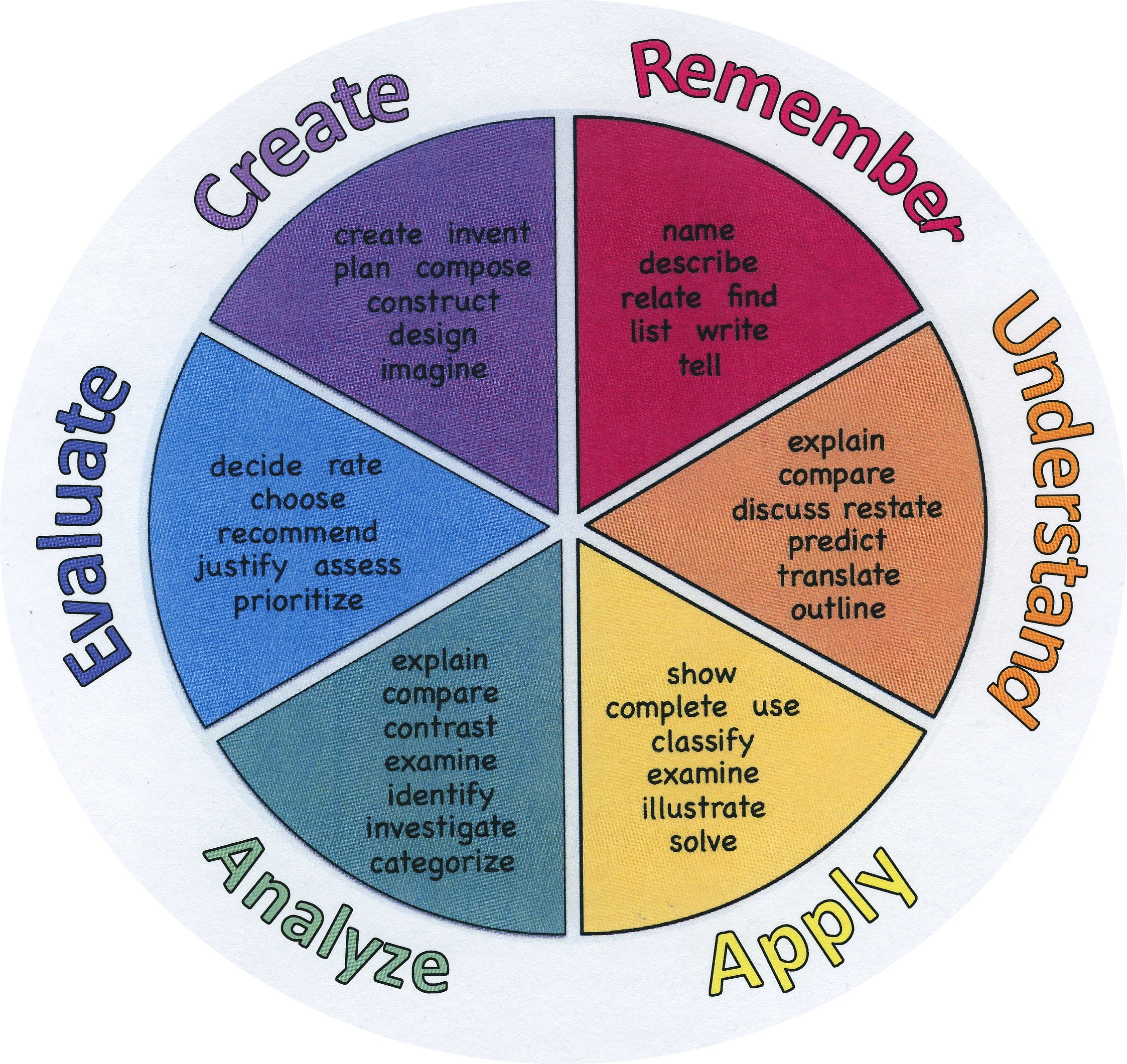

Partly what I missed in terms of leveling my courses was a utilization of Bloom's Taxonomy. I had learned about Bloom's Taxonomy in college and probably even had to implement it for some course work. But honestly, it got lost among everything else. Now, I know that when I create an assignment and its assessment tool, I need to think about Bloom's Taxonomy.

First step, am I at least moving beyond remembering? Remembering is the start of learning, but it can't be where the lesson ends or where the assessment ends. That horrible work I did my first year often stayed on the first level no matter which class it was. Does it matter if a student can match definitions or even write them from memory if she can't restatement or use the terms? It isn't much use if a student can remember what a fragment or run on are if he can't remove them from his own writing. Essay writing is fabulous in this respect because it forces students to move beyond remembering and understanding to at least applying. A real high school level essay does more than restate content.

Of course, the whole concept of an essay was another area of struggle. I taught freshmen, so none of them had written an analytical essay, no matter their level. When all the students are learning the content for the first time, how to do I make it "harder" for the higher leveled class?

- Pace. A teacher can always move slowly for the struggling students, and faster with the advanced students. But, this assumes that just because you are "smart" you learn or work quickly and vice versa. I can personally attest to the falsity of that assumption. Part of what drew me to an English major was the analysis had nothing to do with speed. As a dyslexic, I did not read fast, but that didn't matter in how I thought about the content. Its true that an "honors" level course can move more quickly, but it is more because of the generally better class behavior, the homework completion, higher levels of attention and participation. There are many top tiered students who need extensive time and practice to master new complex content. Most of my core content (citing and thesis statements) took both sets of students the same amount of time to master, which was the whole year.

- Materials. Provide different leveled courses with different materials to preform the same tasks. Say your goal is to write an essay with a thesis statement supported by evidence. Both courses can have the same goal assessing the grade appropriate new material. The texts being used can be different such as Hunger Games versus 1984. Or even, watch Star Wars versus reading Joseph Campbell, then write an essay on archetypes.

- Depth. Animal Farm or Harry Potter are great examples of using depth. There is a surface story which allows plenty of discussion about character, style, and theme. Meanwhile, more advanced students can look at the same text on a much higher level of analysis, using much more content specific lens or themes. Yet, the end product remains the same: an essay with a thesis and support.

- How much? Much like pace, its traditional to just give advanced students more work. Write longer papers, read more pages, do more practice problems, provide more examples, use more sources. Unless the increased depth is also required, this is unproductive. For some skills, more is just fruitless for any skill level. If you don't know how to diagram a sentence, asking you to do two times or twenty times won't make a difference; if you do know how, the number of times you do it doesn't change your learning either. With other skills, such as general reading and writing skills that are refined through practice, its probably, though not absolute, that higher tiered students are not the ones who need this practice the most, so why are they being given more?

- Support. One piece of baggage I carried from my education was that providing supports somehow lowered the rigor. For most cases, I now no longer believe that. At first, when a special education student was allowed to use notes on a test as an accommodation, it seemed unreasonable. But as I learned that many accommodations are just best practices, I started to see things differently. What if we let everyone have their notes? Well, that changes the assessment. I'm no longer going to ask students to restate content and I've been pushed to increase the rigor of my course, not diminish it. Why not let students work collaboratively to reach goals? Why not increase feedback from the teacher? I've become a strong believer in gradual release, and that theory requires lots of supports in your teaching until students reach the mastery level. A teacher can remove supports for higher categorized courses and add them to lower ones, but to what purpose?

- Last stop of Bloom's. When a teacher needs to cover content, she can decide where to stop on Bloom's Taxonomy. Maybe applying poetic literary terms is enough for one level of students to cover the material, while a second group stops only after they have evaluated the poetic literary terms use. Its unclear which skills equate to covering the content sufficiently and how we decide it for which students, but we must ask: Do the students grouped in the lowest level have opportunities to practice the higher skills on Bloom's Taxonomy? Never allowing these students to move beyond remembering and understanding is a disservice.

- Move up a grade level. A good example is that I typically wouldn't actively teach academic freshmen essay organization structures outside a five paragraph essay because, at my school, that was sophomore content. But, I did teach this to advanced freshmen as necessary. If individuals or groups of students in the class were ready for the material, I would be begin to teach the content for the next year as it suited their intimidate needs and interests. They had mastered the goal for their grade level, so we moved to the next one early.

A former collegaue commented on Facebook today that the golden rod is out early provoking his allergies. Having little personal experience with golden rod, I remembered a poem I was forced to memorize and recite in the fifth grade containing a line on golden rod. Why did my teacher have me memorize this poem and several others for recitation? Was it a throw back to old fashion practices of recitation? Were other skills being assessed of which I was unaware?

I'm left wondering, is there value in memorization? Yes, some content needs to be memorized. Sight words when learning to read or basic math facts such as the multiplication table. Do students need to know all the states? I'd say, yes. The capitals? I'd say, no. But how do I make that distinction? It seems to come down to what we as a society consider a solid base of common knowledge. And then, is it my job to make sure students become citizens with this knowledge base or that they can preform the higher levels on Bloom's Taxonomy? Are the higher levels just for "honors" students? For me, these questions are what makes creating a curriculum and differentiating it for all students so difficult, because it is my job to make sure all students have the knowledge base and the ability to apply, analyze, evaluation, and create.

I sure as hell wasn't getting anyone anywhere matching titles, authors, and plot summaries.